The title of this article sounds rather ordinary, but in fact there’s more to say than you might expect. There aren’t a lot of new facts here, but we bring together several strands of argument that don’t tend to be followed to conclusion. It’s useful to think step-by-step about prosperity today and going forward.

- Our national standing today is largely determined by technology.

There are many aspects to this. The most obvious one is the role of high-tech companies in the economy. The NYTimes had an article a few months ago (on the occasion of Apple’s becoming the first $1 T company) with graphic displays showing the size of Apple (as well as Google, Microsoft, Amazon, and many others) in the US economy. The dominance of high-tech is unmistakable. That’s what supports our standard of living and always has. Railroads, steel, automobiles were all high-tech in their day. (Note this is not saying that Google or Facebook are angels, it’s our national strength in technology that matters.)

It is only because we are on top of that heap that we have the money that supports the rest of the economy. That includes much of small business and service industries. It is from the strength of our competitive economic position that we can pay for the non-competitive industries we choose to support. The aluminum and steel tariffs are being paid by us from the industries that don’t need them. To state this somewhat differently—we are not going to build a dominant economy by selling each other stuff anyone can make at artificially high prices.

It’s also worth pointing out, given all the discussions of the military budget, that the technology argument applies in spades for the military. Building new aircraft carriers is not going to make us safe. One only has to think, theoretically of course, about the effect of a North Korean virus disabling the military’s command and control. From the chart below, it is obvious that our level of military spending ought to quash everyone else hands down if money were the only object. But it’s not doing the job, because that’s not the game anymore. And it’s not just AI, it’s across the board.

What all this means is that the people who support our technology position are critical resources who matter to all of us.

This is a lot less elitist than it sounds, because it’s not saying we shouldn’t care about or value everyone else (more on that later). The point is that we shouldn’t be spending our time worrying about who is or isn’t supplanting whom. Our success depends on nurturing and exploiting the best and the brightest—at least for these skills—and we had better spend our time trying to find them and encourage them, regardless of race, gender, or sexual orientation. And if foreigners choose to come here and establish successful startup companies—mostly in high tech—we should be happy they do. It is a major strength of the US economy that people find the US to be the best place to realize their ambitions. We erode that strength at our peril.

Anger at elite technologists may be natural, but they are the wrong targets. Their effect on the rest of us is positive. What we need to avoid is a two-tiered society of haves and have-nots, as we’ll discuss later.

- Businesses today are different from the past in important ways.

Since we’ve identified the key role played by the tech sector, it’s worth thinking about what kind of businesses those are. So let’s take a quick look at Google, Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, and Facebook.

– A first point to notice is that they are all some form of monopoly. This is not surprising as they are all (even Amazon and Apple) essentially software companies. Software businesses invite monopoly, because costs of production are minimal. In such cases, research and development costs become primary, and the company with largest market share can afford to offer products with more features than a smaller competitor can. As automation continues, particularly with AI, similar arguments will apply to much of the rest of the economy.

Managing monopolies is a serious issue:

Monopolies squelch competition. It is imperative for our success that established companies can’t limit the innovative power of new entrants. That has been our historical advantage over foreign competitors and is a major factor in any discussion of how we deal with the rise of China. This is not just a problem with Google, etc. The demise of Net Neutrality is a classic case of giving in to established players, in this case the major telecom carriers.

Monopolies take more than their share of our money. Monopoly power limits price sensitivity. Since the determining feature of competition is more often uniqueness more than price point, products are priced at what the market will bear—as with the iPhone or patented drugs. Furthermore, through manipulation of assets including intellectual property, hi-tech monopolies have been tough to tax. Apple’s success in this is legendary. Their windfall from the recent corporate tax cuts is something to behold (and unnecessary as a spur to investment). It is imperative we learn how to tax monopoly-level profits.

– Next, personal success in these companies requires a high-level of technical competence. Amazon is obviously a case in point, with two completely different populations: the mass of box fillers versus the corporate staff. Note that technical competence is not just a matter for developers, but is also required for the many people in management, support, administration, and even sales. As just noted, as automation proceeds, this trend will extend well outside of high-tech.

This represents the threat of a two-tiered society, as discussed earlier. As a country this implies at the very least a basic responsibility for broad-based solid education and a livable minimum wage.

It should be emphasized that strengthening of education is required for both national success and personal prosperity. Regardless of what advantages we have for staying on top of the heap, we cannot succeed if we don’t have the people to do it.

– Third, all of these business are intrinsically international. With the growth of the world economy (and China in particular) economies of scale are such that we have to think in global terms.

– Finally our fourth and last comment for this section is about a different trend not limited to high-tech—the institutionalized irresponsibility of business. It has become gospel that businesses have responsibility only to their investors, and all other considerations are more or less theft. Businesses used to care about retirement, healthcare, training, even local charity. But current reality is that if someone is going to care about those things, it’s out of the question for it to be them.

In addition, because of the sheer size of the country, the US more than anywhere else has to deal with the phenomenon of towns or regions where the economic base can just disappear. Company town are the obvious example. In an age of accelerating technology change, we can’t stop such things from happening. And we can’t expect rescue to happen by all by itself.

However we emphasize this isn’t just about charity. In the current state of affairs, the private sector is not be doing what’s necessary even to provide the environment for its own success.

That leads to the next topic—what do we need for national success?

- Our infrastructure problems mean more than we thought.

Infrastructure has to be thought of as whatever is necessary for national success and personal welfare. I.e. much more than roads and bridges. The educational system fits in this category as it is required for both personal and national success. Declining upward mobility and the student loan crisis are two indications that there is a lot that needs to be done.

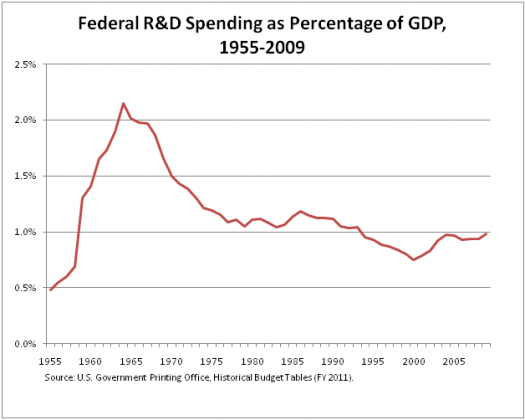

Support for theoretical research is in the same category. It is precursor work for new technologies before they are ready for business. A point worth stressing it that it is not only the research itself that is important—research work assures that there will be a population ready to exploit new opportunities as they arise.

Continuing on, we list a few more significant infrastructure projects needing immediate attention.

– The American Society of Civil Engineers keeps a web site with a break down of national infrastructure requirements. We currently rate a D+.

– To that we add the urgent needs of combatting climate change, which will be considerable, regardless of how the final plans work out.

– Healthcare is currently in flux with ACA under attack and nothing to replace it.

– Finally we have the general specter of a two-tiered society, with all the misery and threat of conflict that represents. That too needs to be dealt with as a national problem, and there’s no one in this picture other than government to do it.

Government’s role in this picture is three-tiered:

i. Government needs to make sure everyone has the education and access to the opportunities to succeed.

ii. Government needs to support what is necessary for national infrastructure, much of which will not happen spontaneously in the private sector.

iii. Government needs to supply a last-line safety net for those who fall through the cracks.

This is a non-trivial task, and we emphasize that the biggest part of it is not charity. We have a current mismatch between a dearth of good jobs and a growing backlog of infrastructure needs of all kinds.

From the point of view here our much-discussed infrastructure needs—back to the roads and bridges—have to be viewed as bellwethers. The fact that we can’t deal even with roads and bridges means that we have a fundamental problem funding the common good, and we have to take that head on.

- There is a mismatch between the needs of our country and the forces that currently control it.

The governing ideology of this country is simple to summarize: let the private sector do it and get out of the way. All government regulation is bad, and taxes are just a brake on the private sector’s ability to make everything great.

The chief beneficiaries of this policy are the ultra-rich funders of the Republican Party, although the problem of money in politics (especially after Citizens United) transcends parties. In this enterprise Trump is largely a front man for the real forces running things.

For these people, with fortunes going back even into the nineteenth century, it’s natural to regard the country as a money-machine. Taxes, regulations, and government services—except for the military—are deductions off the bottom line.

The problem with that view, even for them, is that it is the wrong model for the world we just described. That set of policies would make sense in an extractive economy, where all that is necessary for success is a cadre of imported experts to arrange for pumping oil with purchased technology. In that case you don’t need much from the national population in order to collect the proceeds.

That’s not our situation. As described, we live in a technology-dominated world where the population must earn our national success. For that world we’re currently going in the wrong direction. Devaluing education, denying climate change, cutting research, encouraging xenophobia will get to us sooner than we’d like to think. China is a formidable challenger.

However, it not so hard to be optimistic if we can just be serious about what needs to be done. We have all the tools for success: the money, the work to be done, even the means to avoid a two-tiered society.

The story is not complicated. If we can return to exploiting our strengths, then we should be able to remain in the technological forefront for our chosen areas of focus. If we can control the monopolies, then the associated margins in an expanding world economy should yield money enough (if we can collect it) to produce a workable society for everyone ready to participate.

There is certainly no shortage of work in the infrastructure area, and it needs all kinds of people. In this respect the Green New Deal may be too glib in pinning everything on climate change, but their basic idea is correct. If we play our cards right, the high technology future will provide the funds to support the infrastructure for its own success and for the prosperity of the nation.

We should not underestimate the job. Careful and transparent planning is critical—defining exactly what needs to be done to support both the economy and the population. And then determining how that work can be best supplied.

It should be emphasized is that we’re NOT talking about socializing away the free market economy. If there’s one bad misconception that needs to be hammered down everywhere, it’s the idea that the private sector is magic for all problems. We’ve just gone down a long list of things it’s not going to do.

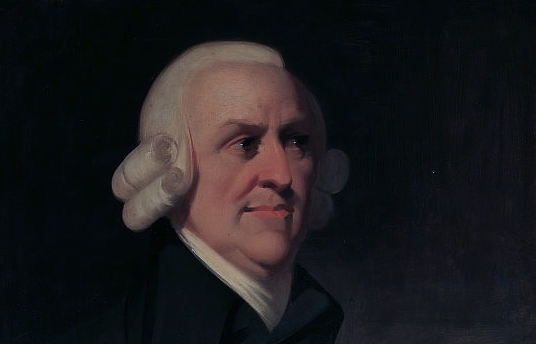

Even Adam Smith was clear about this from the beginning. The private sector is a participant in the public economy, but that economy will deliver the benefits of a free market only if #1 government keeps the private sector from corrupting the markets (e.g with monopolies and bribes) and #2 government provides the resources (e.g. education and other infrastructure) necessary for success. That’s the definition of our job.

This will necessarily require a renewed focus on government and public service. It’s interesting that a couple of recent mainstream books (Volker, Lewis) have recognized public service as an important issue. In that respect “Green New Deal” isn’t a bad term: we need to be as serious as Roosevelt’s brain trust in planning for the next stage for our country’s future.

This is a battle both old and new. In Smith’s words, “The interest of [businessmen] is always in some respects different from, and even opposite to, that of the public …The proposal of any new law or regulation of commerce which comes from this order, ought always to be listened to with great precaution, and ought never to be adopted till after having been long and carefully examined, not only with the most scrupulous, but with the most suspicious attention.” Wealth of Nations is only achieved when government does its job.