This note is an update to the climate change article from last year. The story hasn’t gotten any better, but there is enough that’s new to warrant a revisit.

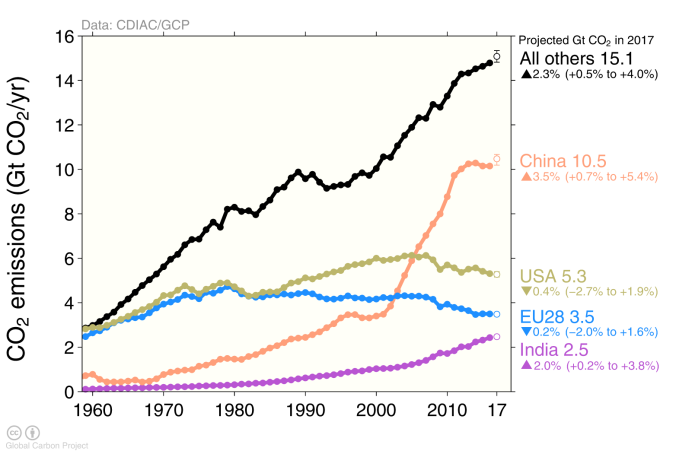

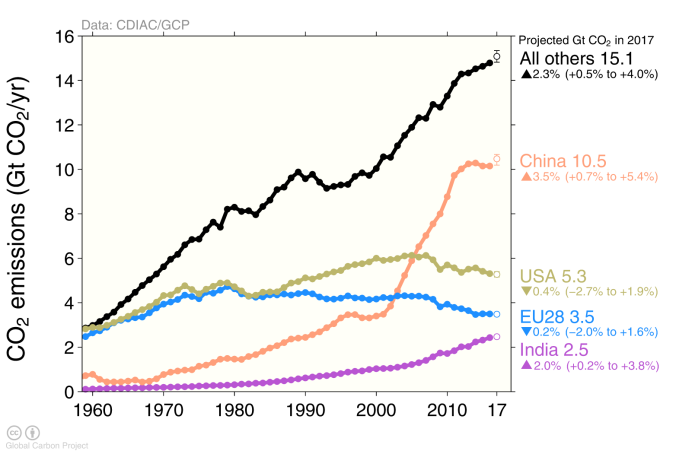

The most fundamental piece of bad news is the opening figure, which comes from the Global Carbon Project. After three years of seeming stability, the world production of carbon dioxide increased significantly in 2017. (The figure says “projection” just to indicate that the final computations are in process.) Without too much evidence we might as well call that the Trump bump. As we noted last time, worldwide unanimity on climate change is important precisely because the advantages of cheating are so obvious. We—with probably the most to gain from the Paris Agreement process—are the cheaters in chief. So it’s not surprising others will have fewer second thoughts as well.

We have to put this change into perspective. Even a stable value of CO2 emission means things are getting worse, because it is the total amount of CO2 in the atmosphere that drives temperature change, and it all adds up. The stable value was attractive, because it seemed to indicate that CO2 had finally peaked and might start to decline. And the decline might mean the total CO2 could be bounded. We’re now back to worrying about the peak, with no idea how bad things will get.

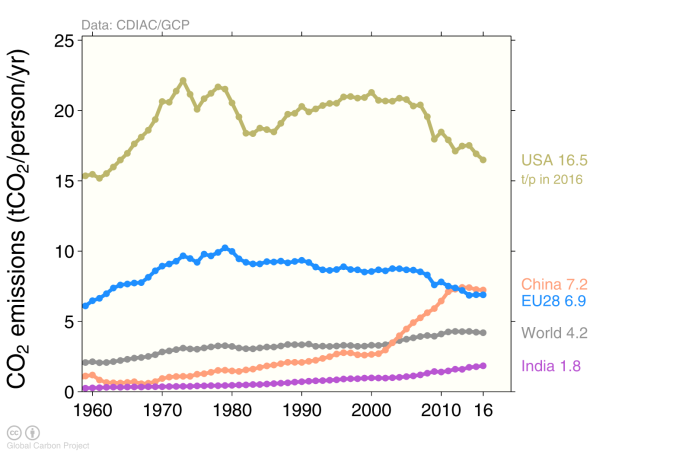

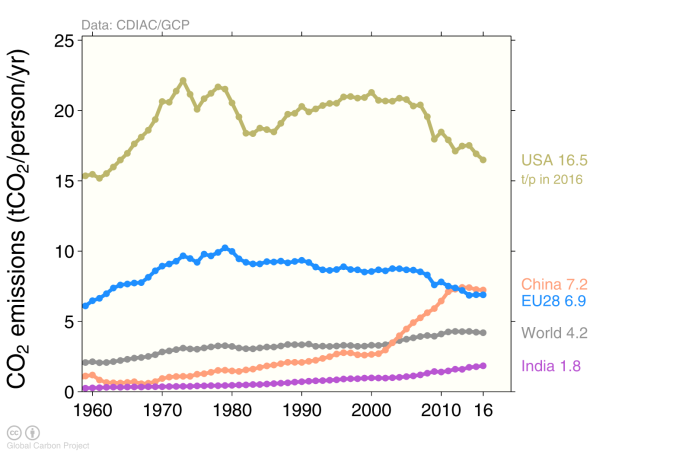

Two more new slides from the Global Carbon Project show what we stand to gain from Paris Agreement unanimity. The first shows the current per capita production of carbon dioxide.

As has been true for many years US per capita usage sits way above everyone else, more than twice both Europe and China. That is a direct expression of our carbon-powered standard of living.

The second slide shows who is going to have to make changes to protect that US standard of living from the effects of climate change.

This shows that the major growth in carbon dioxide production is not from the biggest economies (note that even China has stabilized), it’s from the have-nots trying to achieve some fraction of our standard of living. We are asking them to ignore not only our past exploitation of fossil fuel resources but even our current high per capita use and to delay their own immediate hopes for a better life in order to make the world a safer place for everyone. So much for the question of who benefits from the Paris Agreement process!

That introduces the next topic—public attitudes to climate change. There were enough strange weather events in the past year to give people pause, so we’re getting close to—but still not over—the hump. The latest poll numbers have both good news and bad. First the good news:

Overall, 45 percent of those surveyed said global warming would pose a serious threat in their lifetimes, the highest overall percentage recorded since Gallup first asked the question in 1997. Despite partisan divisions, majorities of Americans as a whole continue to believe by wide margins that most scientists think global warming is taking place, that it is caused by human activities and that its effects have begun.

Then the bad—the improvement is only partisan:

Gallup asked whether people agreed that most scientists believe global warming is occurring, and 42 percent of Republicans said yes, down from 53 percent a year earlier and back to a level last seen in 2014. Just 35 percent of Republicans said that they believe global warming is caused by human activities, down from 40 percent.

This seems like another proof of a much-discussed feature of human nature—when people are confronted with proof that their beliefs are wrong, they double down on defending those beliefs. Unfortunately those are the people running the show.

How can that turn around? A recent Steven Pinker book made an interesting point. Much of the rhetoric around climate change focuses on conservation and a new world view of collective responsibility. But conservation actually isn’t the main point—since we’re not repealing the industrial revolution, the main point has to be new energy sources. We’re not creating a new world where no one drives Chevy Suburbans anymore, we’re just changing the power source. Conservation, however important, is about buying time until we can get there. Perhaps that’s one way to get climate change out of the culture wars (as it should be).

In any case the focus has to be on the reality of climate change, and everything else is tactics. With tactics it’s easier to be bipartisan. One indication is that Congress, over Trump’s objection, passed a bill continuing tax breaks for solar, nuclear, geothermal, and carbon-capture projects. This effort united left-wing and right-wing approaches to climate change largely under the radar. However, it must be recognized that even with such efforts the US is now lagging far behind in support for the technology of climate change.

Carbon capture (separating out CO2 and storing it underground or elsewhere) deserves some special mention, because it has become a bigger topic in the past year. On one hand this is an idea that has been around for decades without going very far, and what’s more the coal industry supports it as a lifeline. On the other hand the technology seems to be improving, the Obama administration supported it as a transitional technology, and even the IPCC climate studies assume some form of it will be used. It currently exists as an expensive add-on for power plants, and some still-speculative variants have been proposed to pull carbon dioxide straight out of the air. Both the power plant and out-of-the-air applications have a common need for CO2 storage technology, of which there are many variants.

The biggest issue with carbon capture is that it can be (and is being) used to delay doing anything about climate change—why worry about carbon getting into the atmosphere if we’ll pull it all out later. The problem is that the technology still has such big questions about cost and scaling, that “later” could be very late or never (and some effects, such as melting glaciers, are irreversible). Even the cheapest estimates say it will cost continuing trillions. What you have to say is that the technology investment is necessary and at worst it at least gets the climate dialog past the hoax stage. And if we could just get the Kochs interested in that business (which is largely oil industry technology), it would settle the Republican perception of climate change once and for all!

Returning to reality, we have to conclude the past year seems like a pause for progress. After Trump took the US out of the Paris Agreement, many wanted to talk about all that could be done to maintain momentum nonetheless. The chart at the beginning shows the limits of that point of view. There are other indicators as well:

– The auto industry’s step back from future fuel efficiency standards

– Exxon’s declaration that climate change is no risk to their profits

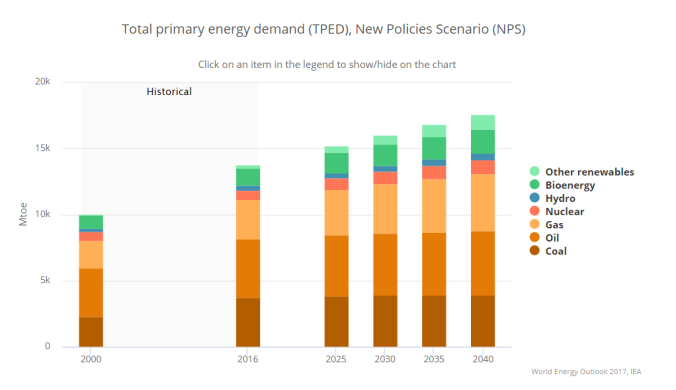

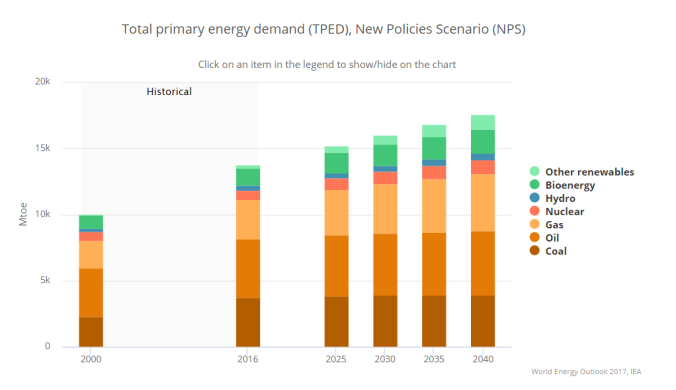

– Business as usual in the International Energy Agency’s World Energy Outlook:

– Even the new preoccupation with carbon capture has to be viewed as a vote of no-confidence in the progress of conservation. If prevention isn’t going to happen, then repair is all we’ve got.

What’s more than there has even been a preoccupation with a more drastic step, so-called geo-engineering. This means injecting chemicals or particles into the atmosphere so as to dim the sun and cool the earth despite the increasing CO2 concentration. There are many risks: continuing ocean acidification, reduced photosynthesis and food supply, and weaponization of the technology. Since CO2 would continue to accumulate, any loss of protection would have disastrous effects. These are desperate measures.

As to what we should be doing, the picture is not too different from last year, but we can be perhaps more explicit.

- Because burning carbon is now recognized to have definite costs (i.e. whatever is necessary to counteract the CO2 increase), we need some kind of carbon tax so that the free market economy can react correctly. Since that cost is not currently captured, our economy is incurring a significant distortion that needs to be fixed.

- We need to get back into the Paris Agreement process to return focus to the goal. To repeat the obvious, the Paris process was always intended to be iterative—with countries readjusting their goals to eventually reach the target. We’re only at step one, so we had better help the world get back on-track.

- We have to recognize that at this stage we’re in no position to judge winners and losers among contributing technologies. So the solution has to be all of the above: nuclear, solar, wind, geothermal, batteries, carbon capture, even substituting gas for coal as a temporary measure. The IPCC gave us what they called a carbon dioxide budget—the amount of CO2 we can add and still stay below a global temperature rise of 2 ⁰ C. In 2014 (the year of the report) it was 800 giga-tons. It is now below 700.

- People have to recognize that despite confusing news reports, we are all in this together. Some people will be hit by sea-level rise, some by drought, some by sheer temperature, some by storms, some by an effect we haven’t seen yet. Some may even be a little later. But ultimately there’s nowhere to hide, and even “later” comes fast.

- There is no excuse for not funding research in all the contributing technologies and also research to understand the climate effects we are going to live with for however many years it takes to get past fossil fuels.

- Ideally all elements of society should be involved in planning such major changes. The carbon tax will help make that happen, but it’s not the whole story. We can’t keep fighting about this.

This administration likes to talk about itself as bringing business practices to government. The evidence for climate change is such that any reasonable business would be doing its best to quantify the risk, so as to take appropriate action. Businesses that choose to ignore disruptive new technologies or entrants are the ones that disappear—along with their disparaging comments on how the new stuff will never amount to anything.

Unless we choose to wake up—that’s us. We’ll act now or pay far more dearly later.