“Boris” by Raymond Wang is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

There is no way to avoid talking about the horrors of the British election. With the confirmation of Brexit and the triumph of Boris Johnson, we have all stood witness to the disgraceful demise of a nation now left only with dreams of past glory.

For us though the important question is about what it means for our own election. On that point the discussion has been generally limited to one question: Does it say we should worry about the Democrats going too far to the left? That one is hard to decide, since Labor leader Jeremy Corbyn was so unpopular for his own sake.

However, that being said, there is still much to discuss. We propose three points:

- Catastrophes not only can happen, but will happen if we don’t watch out for them.

The Democratic debates thus far have played out largely as conflict between the center and left wings of the party. That means essentially all of it has been fought in the never-never land of post-Trump. That’s not the same as working on viable strategies to win.

This will be a very tough election, fighting the Fox News, the Electoral College, incredible amounts of Republican money, and all the (legal and illegal) powers of incumbency. Most candidates have done a reasonable job in providing position papers for what they stand for. They need to tell us how they’re going to win.

- We need to recognize that the electorate isn’t convinced of the urgency of change.

In Britain, Corbyn’s big socialist revival was not so much wrong as a non sequitur. What actually was all this trying to solve? Why was it an argument for change? It was ultimately a declaration of irrelevance.

We have a similar problem. The very first question of the very first debate has never been adequately answered. Elizabeth Warren was asked (more or less): “Why are you proposing all these changes when—by all polls—the vast majority of Americans think the economy is doing fine?” That’s a question for all Democrats—what is it that’s so bad that we need change?

Warren’s answer—about radical inequality—was nowhere near strong enough. It essentially said that all those people who answered the polls were just wrong. But no one else has done better. Healthcare was a great issue for the midterms—that’s something broken that we’re going to fix. But it’s not enough to unseat Trump. Impeachment doesn’t touch peoples’ lives directly—it’s about an abstraction called democracy. Even climate change comes across as an abstraction, although it’s part of what’s needed. Democrats need a short, clear reason why people need to worry that there is something that needs fixing.

That’s a bar to be passed before we can begin to get traction with specific plans for change. Until then, like it or not, “fundamental structural change” will be a negative.

- We have to keep this a referendum on Trump.

Corbyn pretended Brexit wasn’t the main issue and went off with his own program. The public was unwilling to follow.

Regardless of how broadly we see the issues, this election is about where Trump is taking the country.

We need a well-defined Trump story to challenge Republican claims of a great rebirth of the American economy. Even on trade they’ll do what worked for George Bush on Iraq—we’ve been through all the pain, don’t miss out on the rewards!

That means we need to show what four more years of Trump will actually mean. And how to meet the real challenges for our future. It seems helpful to think in terms of personal and national issues for the voters:

Personal well-being

Healthcare (complete failure of vision)

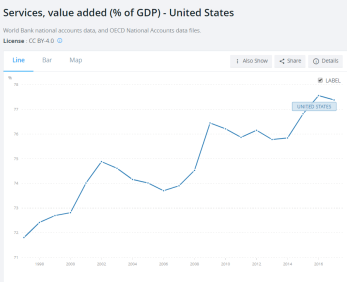

Decline in good jobs (manufacturing, good jobs in general)

Education (no initiatives, no funding)

Income inequality (all growth for the rich)

Guns (unsafe to be in school!)

Climate change (what world for our children?)

Women’s rights trampled (bodies owned by the government)

⇒ Worse life for everyone but the protected few

National well-being

Eroding technology dominance (science marginalized)

New businesses sacrificed to old (Net Neutrality)

Losing out with climate change denial (ceded primary position to China)

Weakness with China and North Korea (situation is worse than ever before)

Nuclear proliferation (a danger in all directions)

Racism and divisiveness undermine our strengths (just what Putin ordered)

Demise of democracy (our major source of prosperity and power)

=> Welcome to the Chinese century

That’s where we’re going. For our own dreams of past glory.