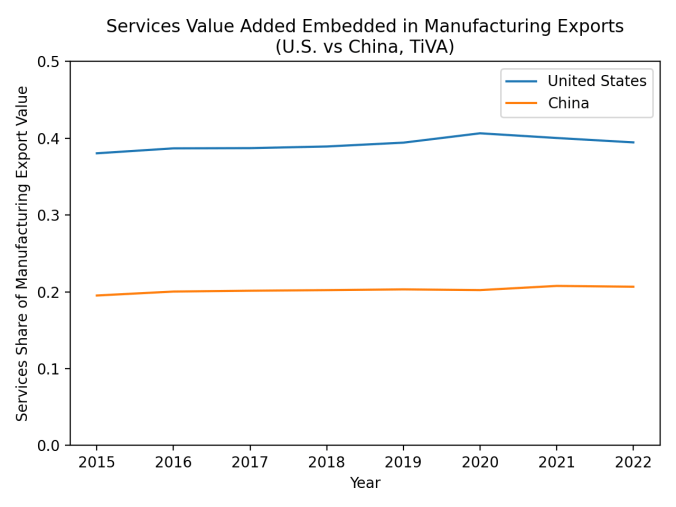

We all know about the huge US trade deficit with the rest of the world. Most of us know this is just about trade in goods, so that it does not include the trade surplus in services—which historically compensates for roughly 40% of the total deficit. So services are large and growing but nowhere near the size of the problem. What’s less obvious is just how wildly incomplete this story is.

It’s straightforward to see why. Look at the iPhone. iPhones imported into the US are a significant (but of course not decisive) contributor to the deficit. It’s an expensive item and we get lots of them. However what’s imported is the hardware—which is what counts for the balance of payments. But great majority of the profit goes to Apple, because most of the product value is from the software written here. The balance of payments calculation is backwards—it’s a win recorded as a loss.

It’s worth noting a historical parallel. Early in the Industrial Revolution the British insisted that India only export raw cotton to Britain, so that all the value-added would be captured there. All parties recognized this as an example of colonial exploitation. We’re in exactly the same position, and we’re worried about the balance of trade!

We can even go a step farther. Consider an iPhone made in India and sold in Korea. It shows up nowhere in balance of payments calculations, despite the profits earned by Apple on every such sale. There is no reality to the balance of payments statistics at all.

And this isn’t a one-off. Here is a list of the top ten US companies by market valuation.

🏆 Top 10 U.S. Companies by Market Capitalization (2026 estimates)

- NVIDIA Corporation – approx. $4.5 trillion (currently world’s largest)

- Apple Inc. – ~$4.0 trillion

- Alphabet Inc. – ~$3.8 trillion

- Microsoft Corporation – ~$3.6 trillion

- Amazon.com, Inc. – ~$2.5 trillion

- Meta Platforms, Inc. – ~$1.4 trillion

- Broadcom Inc. – ~$1.7 trillion

- Tesla, Inc. – ~$1.3 trillion

- Berkshire Hathaway Inc. – ~$1.0 trillion

- JPMorgan Chase & Co. – ~$0.6–0.7 trillion (approximate, rounding into the top decade range)

The #1 is now Nvidia. Perhaps surprisingly it’s just like Apple. They don’t make the hardware either. What they provide is another kind of software—detailed specifications embedded in a form for transfer to TSMC for fabrication. The high-value contribution is made by developers in the US, which is where the profit is realized as well. (It’s interesting to compare Nvidia with TSMC. Both companies have monopoly positions in their markets, but Nvidia avoids the huge capital expenses of hardware, and makes much more money by being on top of the production stack.) There is something more than a little disturbing about national policies based on numbers that are completely off-base for the two biggest companies in the world.

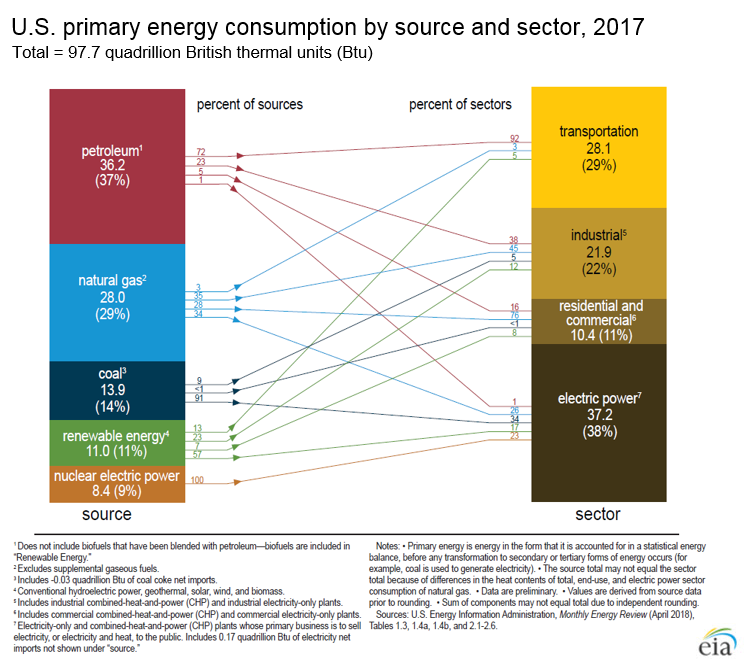

The problem here is that the goods versus services distinction doesn’t mean what we think it does. We want to think about that distinction as somehow capturing hardware versus software, but it doesn’t work that way. More and more software is getting embedded in products, so it’s counted wrong. It’s more correct to think about software (broadly-defined) as highly-skilled manufacture. The same kind of thing happens with pharmaceuticals. More and more of the value creation is not in building the product hardware, but in defining content. So the value-added enabled by the imports is not captured anywhere in trade statistics.

And the software business is great—fewer capital requirements and you’re on top of the heap for revenue. There is also a strong trend to monopoly from network effects and software’s built-in economies of scale. Most of the businesses on the top 10 list—one way or another—are software businesses and many are effective monopolies in their sectors. It’s not surprising our economy has evolved in that way, and the top 10 list is anything but a sign we don’t know how to make money. However since the statistics have not kept pace, we end up deluding ourselves about both the present and what matters for the future.

We can put some numbers on that. What are the actual revenue impacts of the balance of payments deficits? For Apple and Nvida the calculation is straightforward from available product costs. For the iPhone the ratio of enabled revenue to the balance of payments deficit contribution is 5 to 1. For Nvidia the ratio is 6 to 1. Those are big wins, and perhaps less exceptional than you might think. It’s harder to get numbers for US companies overall, but arguing from both S&P 500 foreign sales numbers and OECD value-added statistics gets the ratio of aggregate revenue linked to trade to the deficit at about 4 to 1. (The argument is not complicated. Both approaches yield US foreign sales of about $5.5T which means $2.3T of foreign revenue above all reported exports, both goods and services. That’s real value not captured by the trade stats. Further as a conservative estimate we can assume that same uncaptured value for US domestic revenue by the same companies. That’s now $4.6T of revenue linked to international trade. Divide by the goods deficit of $1.2T and you get 3.8, and the more correct goods + services deficit of .9T gives 5.1). Our true global trade balances are a resounding plus.

So what do we conclude about the balance of payments deficit? First of all it’s NOT a problem. It’s a reflection of the way our economy works, and that’s a proven productive direction. The unbalance is not because we are losing out but because the trade statistics don’t see where we make money. Furthermore this is not a picture of everyone taking advantage of us; on the contrary we have much of the world competing with lower-margin items to supply us in our higher-margin activities.

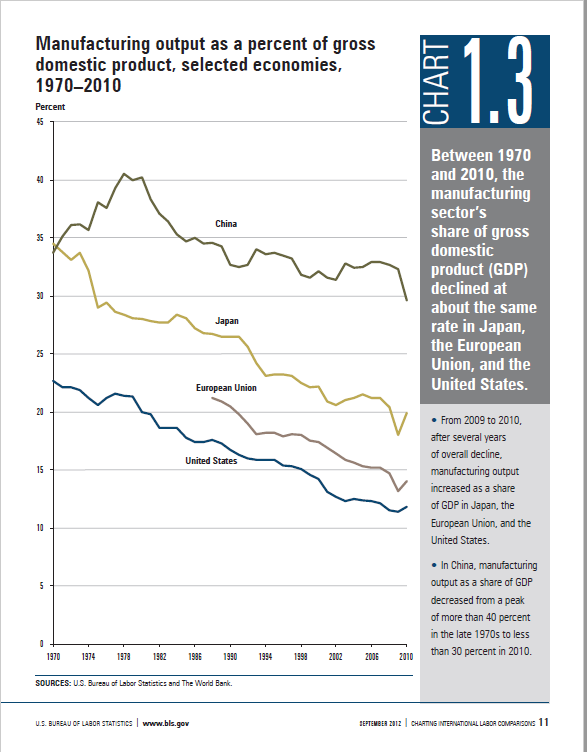

That’s not to say there are no issues—we obviously need to talk about jobs and security of the supply chains. Jobs are the more pressing item. However the only reason jobs are in this discussion is the assumption that people are hurting because other countries are stealing our prosperity through trade. That story is false. People are not poor because we as a nation are not making money—we are–they’re poor because the distribution of wealth in our society has left them behind. The idea that we’re going to solve that problem by having our people substitute for the workers in the low-margin industries that feed our industrial giants is so ridiculous it’s hard to know where to begin. Those aren’t manual labor jobs, and they can only be good wage jobs in this country if the government basically pays their wages. There’s no other way they are going to meet the price targets for the final products. Even then it’s hard to imagine anything practical about these half-governmental uncompetitive companies. What we should do for disadvantaged populations is part of a bigger story about government responsibilities—we’ll return to that later. But this story—solving poverty by bringing low-margin, low-wage factories here—was never more than populist gloss. No one ever cared enough to work it out at all.

As for supply chain security, the argument seems to be that we need to bring all of these supporting activities in-house to make sure that supply chains are under control. That argument is also false. Bringing supply chains in-house is no guarantee. During Covid the CDC had a contract to provide M95 face masks prior to the pandemic. However, the contracting company got acquired, and the bigger company noticed there was no health emergency and no real business. So they spent their money elsewhere and no single mask was ever delivered. Running an artificial, uncompetitive business for reasons of security is anything but a sure thing, and providing a second such business for redundancy is even worse. And again if the business is to be price competitive lots of money needs to be pumped in. It’s an expensive bad solution. Instead what is most useful is real multi-sourcing. We need diversified supply chains with production spread across Taiwan, South Korea, India, Vietnam, and Mexico, so that no single disruption can choke off supply entirely. Instead of competing with those real, productive companies, our interest is in making sure they keep it up.

Just about everything involved with the balance of payments discussion is out of touch with the realities of US economic strength and the needs of the population. Thus far it’s too early to see the full dangers of the mismatch of policy and reality: The final tariffs were significantly lower than originally proposed, so that supply chains have been able to adapt, but multiple studies have shown that the tariffs for more than 90% are paid by us (regressively). And there has been only pain—not benefits—to the people Trump is nominally saving; it’s the billionaires cleaning up left and right. (But at least today we can celebrate the Supreme Court’s blocking Trump’s ill-conceived and illegal tariffs!)

However the future is the main story, which is where we need to go now.

For that we need to recognize just how dynamic the world economy is becoming. There is every reason to believe the trends we discussed for the top 10 list—software (broadly-defined) and monopoly—will continue and even accelerate. AI makes it ever easier to build software that interworks with all kinds of products. And robotics in particular can be revolutionary. As robots become software platforms, rather than individual products, a greater range of businesses can be imagined primarily as software applications. That way the iPhone business model can extend to all kinds of physical devices. AI has already made it possible for small teams to do things that used to require many more people with distinct specialties. We’ve already seen companies come from nowhere in a very few years—there will be more and faster.

How do we prepare for success in that future? The balance of payments view of the world doesn’t help, because it is static and already out of touch with the present. Fixing that gets us nowhere. Further Trump’s rhetoric about bringing back the good old days of factory jobs mixes up corporate value-added with imagined low-skill job creation—for jobs that largely no longer exist! He may want to think about people standing in front drill presses all day, but we had better not take him too seriously. We have to deal with the future as we see it coming

To begin we need to talk just about business competitiveness. If we’re going to succeed in the kind of business environment just described we need three things:

- We need innovative types able to start the new businesses which will make up the rapidly evolving landscape we just described

- We need people who will provide the kind of value-added needed by such businesses

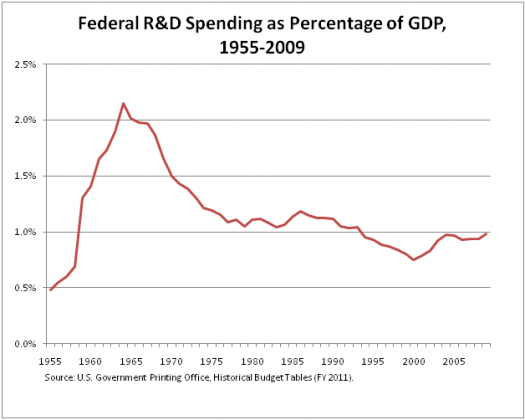

- We need government to support innovation. In practice that means not choosing winners and losers and protecting innovators from the powers that be.

Those are absolute requirements. Before we can talk about anything else, we have to satisfy those. At the same time however we need to provide for the well-being of the population and the national security of the country. Those two types of requirements seem distinct, but as we’ll see they are closely linked.

On the innovation side we have traditionally been well-positioned here. The single most legitimately-true feature of American exceptionalism has been our openness to enable people from anywhere and with any background to find a home where they can thrive and fit in. We have been the place for the best and brightest from everywhere to come and build success. Immigrants and children of immigrants have been prominent for Nobel prizes, in founding companies, and more generally in staffing the high-tech companies driving the US economy. It’s true for AI today. And the strong network of research universities and government labs has meant that the latest technologies could be counted on to be supportable for new businesses.

US openness has been perceived as unique worldwide—which matters for all of us. Because we draw from the whole world, the US achieves levels of technological dominance and wealth that are hard to match. China may be big, but the whole world is a lot bigger—and so are we. It matters in every domain. That not everyone experiences that wealth is a different issue—a political problem (as we’ll discuss later) not a national wealth problem.

The bottom line is that the overall well-being of the population is not just a matter of decency—it’s intrinsic for national success. Our dominance is in a very basic way a reflection of what we as a nation represent.

It’s interesting that China is a kind of opposite pole from us—a huge inwardly-focused country whose export businesses are primarily in hardware with hard-won price advantages. That’s not to say they can’t move in our direction, but thus far their focus has been different, with less emphasis on software value added. As the following chart indicates, China’s exports have been considerably less oriented toward added services than ours. If we’re worried about competition we have to recognize and play to our strengths. Our big world of economic as well as political allies has been of major importance. As in the discussion of imported inputs for Apple and Nvidia, they do their jobs for us better than we would do for ourselves.

All of that is why it is so serious that we have recently decided to relinquish many of those traditional advantages in a burst of self-destructive nationalism. We now have overt hostility to foreigners, attacks on universities, and cancelled research money. We’ll throw lots of money into today’s hottest development item—the current version of AI—but we have chosen to be deliberately blind to whatever comes next. In addition we’ve decided to choose winners and losers in technology based entirely on “intuition”. Since climate change is now officially non-existent, all technologies associated with it are removed from our national consciousness. Unless some of this is reversed we will be like the British after World War II, living in past and lost grandeur.

Beyond competitiveness, we need to talk about national security and population well-being. For both the most important message is a simple one: there are a great many important problems that the private sector will not solve by itself. That may seem obvious (it was to Adam Smith) but it’s contrary to the endlessly restated ideology of the last decades: that the unfettered private sector just needs to be left alone to work its magic. I’ll start with security. We need to be clear—we’re talking about national security here, not the reliability of value chains as before.

Government needs the professional competence to decide what actions have to be taken in the economy for reasons of national security. That includes what products and capabilities we need to have here and what needs to be done proactively to prevent the kind of dependencies we have with rare earth elements today. We have to be able to think ahead in a way that the private sector won’t. So government needs professional competence protected from political persecution. After all, the Chinese clearly were able to think ahead; a primary reason we couldn’t was the ever-present private sector mantra just mentioned. We were too smart to think about government telling businesses what to do.

In addition government needs to think more broadly about security. As we noted earlier we will never be able to take everything in-house, and even domestic suppliers have their own interests. So complete self-sufficiency is a chimera, and security is intrinsically concerned with international relations and the world order overall. That’s a big subject worth discussing but out of scope here.

Returning finally to the well-being of the population, the most important thing to say is that the businesses that form the basis of US economic strength won’t necessarily fix it. They’re not going to employ everybody. To some extent the overall wealth of the country will translate to general prosperity in the domestic economy (e.g. entertainment, home services)—but there’s no way, particularly with AI, that will be enough. It isn’t enough now, which is why we get Trump’s fairy tale with 1950’s jobs. Government will need to be involved with things like an adequate minimum wage as well as a bigger role in infrastructure of all kinds. There is no shortage of work that needs to be done—in physical infrastructure or healthcare for example. Also climate change will require significant near-term modifications all over the country.

That takes money, but national wealth is not the issue. The companies in our top ten list aren’t low-margin businesses even if they’re happy to get tax cuts. And going forward, we’re talking about sector-dominant software companies for even more of the same. The challenge instead will be to restore the idea that shared prosperity is ultimately for everyone’s benefit, so that progress can happen.

It’s a truism that we have to grow the economy and ensure that wealth is broadly shared. But it’s important to recognize the two aren’t the same thing, and we need both to make the economy work. (Stephen Miller’s much-repeated slogan—getting rid of immigrants means more of the pot for all the rest of us—is a good way to fail at both.) This isn’t easy, but it’s not as if we haven’t done it before. Trump talks about the good old days of the 1950’s, but he doesn’t talk about how we got there. That broad-based prosperity was most assuredly not achieved by liberating the miracles of the unfettered private sector; it was by doing what we’re talking about here.

Last time we had to go through the Depression and two world wars to get there. This time we need to do better—both the risks and rewards are too great not to.