The dangers in Ukraine are enough to make one wonder about the current world order. We’d like to believe that it’s beyond the pale for one country to invade and take over another on the flimsiest of pretexts. Despite some current rhetoric, Crimea was not that: it had been an essential part of the Russian military infrastructure for centuries. Ukraine is different—what does it mean?

Regardless of how the Ukraine affair ends, the change it signifies is enormous. In the wake of the horrors of World War II, the US as remaining unscathed power helped put together a system of rules and organizations aimed at preventing another one. The idea was to prevent economic collapse and to resolve conflicts before they became wars. We got a UN, an IMF, and rules to govern international trade. The result was an extended period of world prosperity. The communist bloc stood outside all of that, but even in the days of the Cold War overt seizures of other countries were avoided.

Over the intervening years much of that liberal economic system remained, even as the world became much more complicated. Standards for permitted behavior lived on. In some sense, the Paris climate agreement was a kind of last hurrah. There was no enforcement mechanism, but the idea was that unanimity would shame the cheaters into compliance.

Trump broke that idea in a way that only an American President could. He asserted that there was no reason to obey any of those (US-initiated) international rules, and he got away with it. Until Trump people cared about WTO trade rules, climate progress, and democracy worldwide. Now essentially all of that is off the table. And the powerlessness behind many international institutions has been laid bare. If Putin decides to invade Ukraine, we’re in a world where the only consequences are the ones we manufacture for the event. The UN is manifestly irrelevant. Shaming has no force. There are no rules, and your friends can cover for you. It’s just the way things are. Military threats can be the first not the last of options.

This is a problem generally and for us in particular. Under Trump we developed adversarial relationships with just about everyone, with the view that they were all against us, and we had to show who’s boss. That limits our power. Most serious is what happened with China. Xi may be a megalomaniac and an autocrat, but we empowered Chinese hardliners and contributed to his nationalistic program by delivering threats echoing the imperialist past. When Trump said he would destroy the Chinese economy they took it seriously. The newly-revived alliance with Russia—a thorn in our side for Ukraine—was at least in part our own doing.

We have replaced our successful efforts for peace and stability with a new world view where we need no one, and any constraint on our ability to act is unacceptable. It’s easy to say (and many do say) so much the better. Every country needs to stand up for itself, and all of that international stuff just gets in the way. That’s an appealing slogan. It wasn’t just Trump’s line; it was behind Brexit and all the populist movements of the both the left and the right. However we’re not the only ones playing that game. That “freedom” is a freedom for any country to do anything, and the Ukraine affair is an early indicator of where that goes. We seem to have forgotten World War II and the Depression, and that’s just for starters.

Our own history gives an excellent example of what happens. That ocurred after the American Revolution, under the so-called Articles of Confederation. It took only a few years for the American states that had fought the British together to be at each other’s throats, torpedoing economic progress for everyone. Things got so bad that the states had no choice but to give up power to a new Constitution and a national government. In Europe there were centuries of wars that only ended when cooperation became manditory in the post World War II recovery.

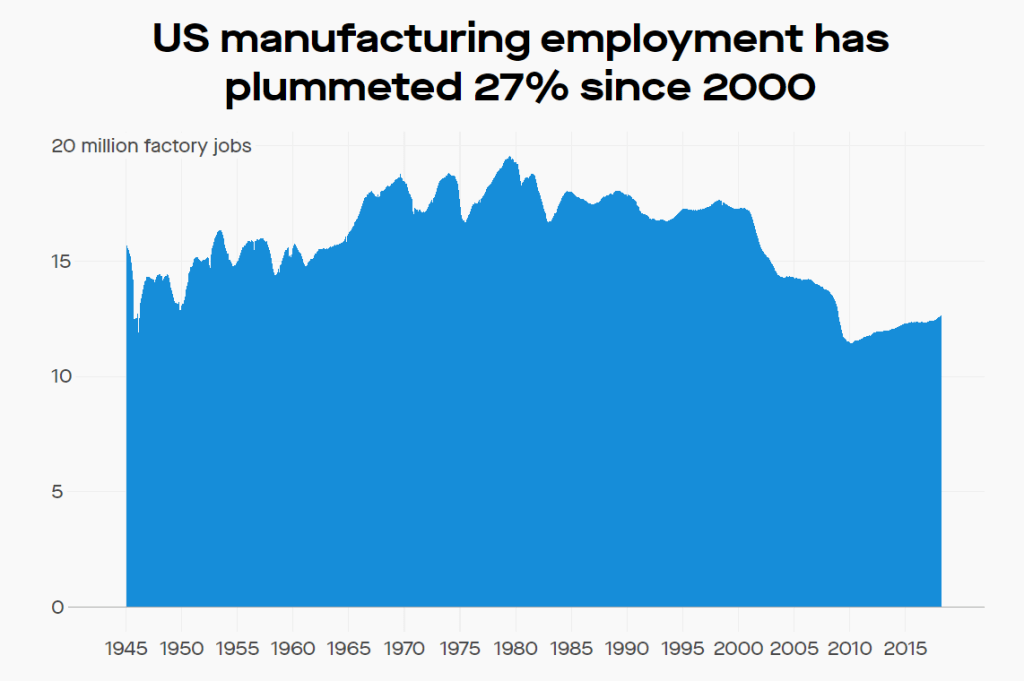

It’s a fact that the liberal economic system has gotten a bad name in this country—”Bill Clinton let China in the WTO and there was nothing we could do about the Chinese assault on American jobs”—but that universally-repeated story is false. (It’s one example of what you might call bipartisan revisionist history—the left and right united against the center!) The main issue raised with China’s behavior has always been currency manipulation, which was in no way permitted under WTO rules. And as the following job loss chart makes clear, the loss of American jobs was 100% a phenomenon of the George W. Bush presidency:

That’s no accident. The radical neocons had us preoccupied with fighting a $3T war, and the same deregulation mania that produced the 2008 crash had us actually encouraging outsourcing abroad. For the business-friendly Bush people cheap off shore labor was good. All subsequent efforts to help the people hurt by that process were blocked by Congressional Republicans bent on sowing dissatisfaction ahead of the 2016 election. The liberal order conspiracy is a convenent fiction for both the right (to cover its tracks) and the left (to attack the center).

If we’re going to avoid economic and even potentially military disaster, we’ve got to get past the electoral propaganda and understand what we’ve done right and wrong. In particular we’ve got to wean ourselves from the siren-call of nationalism. We’re not going to “win” the future, but we can certainly all lose it. The real challenge is getting internationalism right, so that everyone has a stake in the action. We built unprecedented peace and prosperity after World War II. That job needs to be done again before we give it all up—in a way that has happened many times before. Both prosperity and peace are in question.

One important lesson of history is that economics precedes politics. The EU, for all its imperfections, is a vast improvement over centuries of status quo. What got that going was a step-by-step economic union, long before there was anything political on the table. In that sense, strangely enough, you can argue that the WTO is more important than the UN. Getting the WTO back on track is going to take considerable doing, but it has to happen. And perhaps climate change can yield an appropriate model.

Climate change is an unusual situation in that practically every country has veto power of the result. We all share the same atmosphere, and the CO2 concentration is only controlled when everyone cooperates. So the solution has to get a buy-in from everyone, rich countries and poor. In fact it can only work when rich countries recognize that—like it or not—they’re going to have to help the poor ones. Everyone will have to get used to the idea of an international project where the focus is less on who gets the best deal than on whether it delivers the necessary benefit for all.

A functioning WTO is a similar balancing act. As starting point there is one basic reality to be acknowledged: self-sufficiency is not a desirable or realizable goal even for large countries. Despite all the discussion of the evil Chinese, we would be vastly worse off if they just went away. Just in general, we are not always going to be the best at making everything, and our own industry will be crippled if we can’t build on what’s best.

Furthermore discussions of self-sufficiency tend to include a strong dose of the always-dangerous delusion “my people aren’t like that.” In fact domestic manufacture does not guarantee availability, quality, price, or appropriate technology. The single worst problem during the first stage of the Covid crisis was a lack of testing equipment—because the American manufacturer with a CDC contract to produce the tests had decided they could make more money doing something else. Similarly, self-sufficiency can do little to guarantee the well-being of the national workforce, as there is no substitute for government dealing with all relevant labor issues. Trade is more like climate change than it seems—it’s something we’ve got to make work.

The balancing act is in the many factors that have to be taken into account for fair trade: labor conditions, environmental rules, government involvement, and so forth. Those are both impediments and opportunities—they make the negotiations harder, but they are also leverage opportunities for a better world. Elizabeth Warren in her Presidential campaign made a long list of items she wanted to make as preconditions for trade with the US. Her standards were very high—it was pointed out at the time that no country met them—but her list was an indication of potential opportunities. Also, it is important that these rules should apply to everyone—including to us.

What this comes down to is that globalization, despite the rhetoric, is only anti-labor if we make it so—which is precisely what happened under George Bush. Instead of using it to establish worldwide labor standards, we used it deliberately to undermine workers everywhere. In other words thus far we’ve had globalization exclusively for the rich. If we don’t step in to control it, it will stay that way—populist movements or not. And if we don’t start learning how to create a world order for the benefit of humanity, no amount of national chest-beating will save us.

The Ukraine affair is dangerous in its own right, but even more dangerous as a symbol of a world out of control. What the world needs now is neither uncontrolled chaos nor world government, but a set of mutually-agreed rules to forestall a fight to the bottom. As with climate change, there is no way out other than to acknowledge we are now one interconnected world, and we will all either stand or fall together.