Last year this blog had an overview of the major factors involved in fighting climate change. Most of that is still current, but it has also become clear that there is a lot of confusion—even in the climate movement—about consequences. So this piece is not about the basics; it’s about the reality of what it takes to combat climate change.

To start with, Here is a list (off the top of my head) of widely-believed nonsense. There is probably something to annoy everyone. You can see if I’ve made a case for it by the end.

– Conservation is a primary issue

– It’s important to get solar cells on rooftops everywhere

– Recycling is important

– Local initiatives are important

– State initiatives are important

– The main game is getting our house in order

– We don’t need to do anything, since technologists will solve it by themselves

– We’re ready for electric cars to take over the transportation sector

– Current solar and wind are ready to take over everything

– Winning is simple, we just have to stop the oil companies and start deploying the good stuff.

– For climate change employment, we need local communities to decide what they really need

– The private sector is doing it all by itself

– Carbon pricing is optional

– Carbon pricing is all it takes

– We need to get a better deal than the Paris Agreement

– We’re in control of our own destiny

– We all need to change our lifestyles

– Fighting climate change will tank the economy

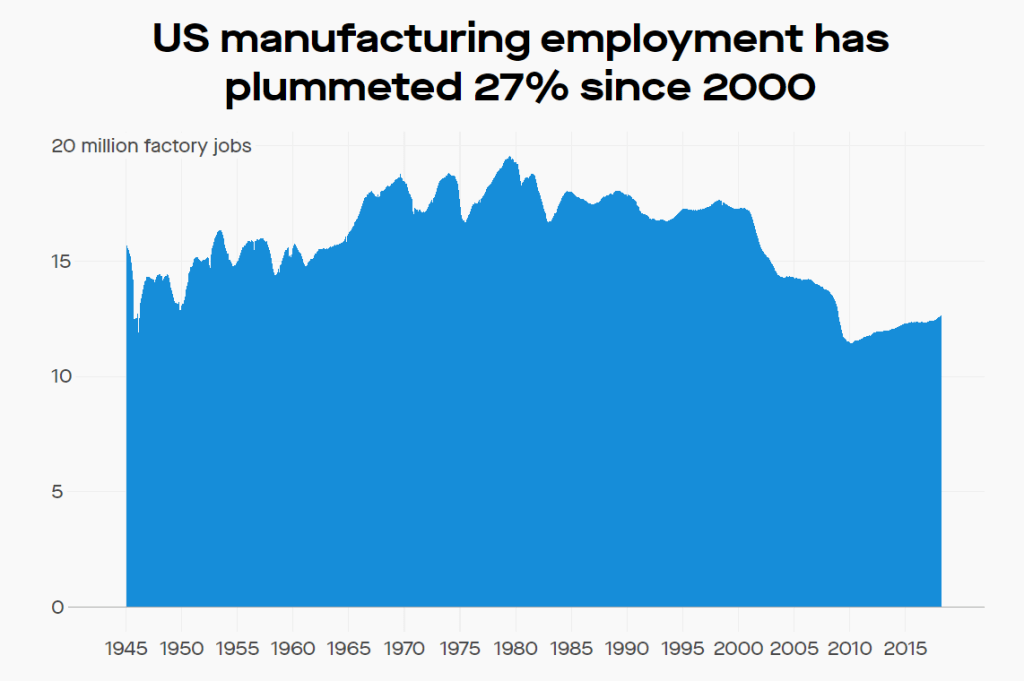

– Economic dislocation means taking care of miners

– Since poor people get hurt worse, climate action is a matter of charity—for social justice

– Same thing for racial justice

– Same thing for regional justice

– Internationally, this is a matter of everyone taking care of their own

– With China and India, the important thing is to stand tough to get what we want

– We have to insist that any new technology developed here gets manufactured here

Let’s start this off with item #1—conservation. From within the US it’s easy to believe the fight against climate change is all about conservation. After all, we’re up against a hard limit on tolerable levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, so we’ve just got to cut down on burning in all ways. And we’ve got to learn to behave differently in the future.

However that logic breaks down quickly. What about all the people in China and India? Our conservation is a blip compared with them, but we share the same atmosphere. Do they just have to get used to the idea that cars and air conditioning aren’t for them? They should accept permanent sacrifice for the good of mankind? Even in the US, no amount of conservation will move people to electric cars or eliminate the CO2 production from heavy industry.

So even for the near-term we have to recognize that the fight against climate change is not primarily about conservation but about alternative energy sources. Worldwide, we need to evolve energy sources, so that there will be enough to take care of people everywhere. As noted in the prior piece, there is in fact no reason to fear we will ultimately lack for power. This isn’t about learning to live with energy scarcity—it’s about creating a future for all people, all countries, and all life styles.

For that reason we need to focus on the transition to alternative sources of power. There are two quite different types of problems to be solved:

– Generating and distributing power

The first thing to recognize is that (despite some obfuscation from the oil companies) the future is electric. That’s the common currency for the energy to be used everywhere, in factories, in homes, in cars. It’s what all the renewables produce today, and what will be produced by all future candidate technologies. Electricity is easily transmitted over long distances, and can be stored for later use (although there is much still to be done for high-volume, in-network storage).

So this work includes the electrical network, the sources of energy, and the means to store it. Since everything will move to the electrical grid, its capacity will need to grow significantly and fast. This is a huge project, but this is ultimately just a matter of national will. That makes it the easier part.

– Adapting applications to use it

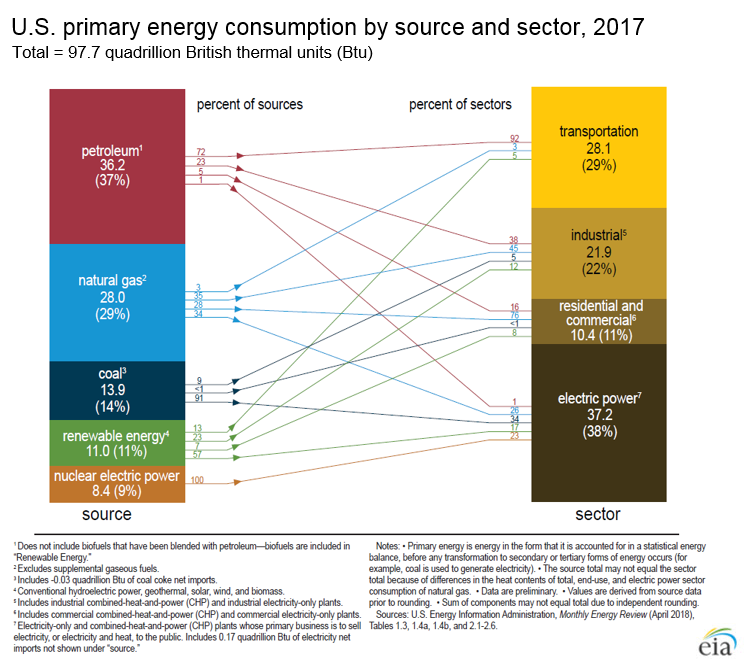

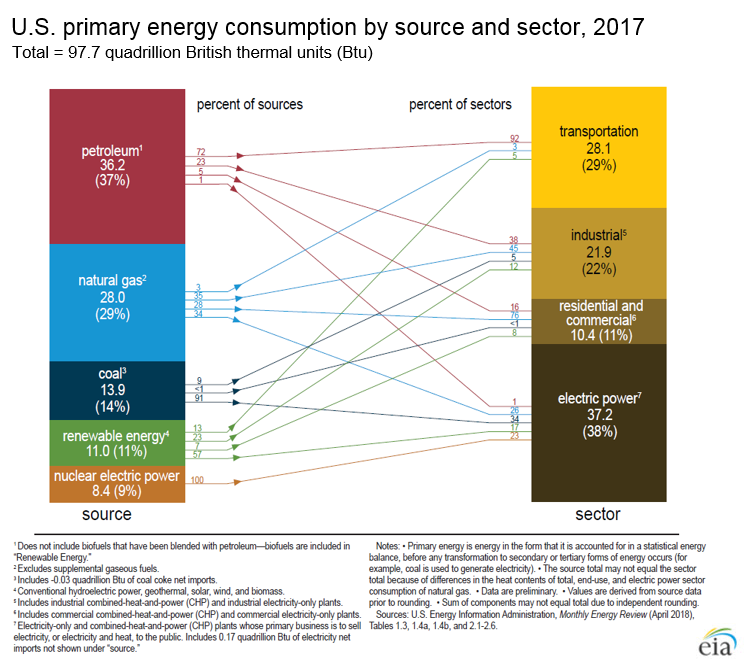

For that you need to work through the major sectors of energy usage. Here is the chart for the United States.

This is a larger and more complex undertaking, requiring careful planning for each sector. Carbon pricing is one of the few actions that can be done across the board. As we noted previously, assuming the atmosphere is free amounts to an annual subsidy of $1 T to the US fossil fuel industry. Even low-level initial pricing (as with CCL) sends a message for corporate planning. However, it is naïve to believe that carbon pricing will just take care of all sectors in time to avert disaster. Note also, for priorities, that the residential and commercial sector is the smallest by far.

We also have to think about this problem not just for the US but for the rest of the world as well. The US Energy Information Agency has released a document that helps in thinking about that task. (A short summary of conclusions is available here.) It has projections of energy use throughout the world going out to 2050. With that it includes variants of the US energy use chart (just given) for other countries. A significant fact is that many developing countries have a proportionally much larger industrial segment than we do, as high as 70%.

The report shows some influence of climate concerns, particularly in the US and China, but overall it describes the dimensions of a disaster. The following chart taken from the report shows a continuing growth of CO2 emissions for the entire period. While the report itself doesn’t explicitly call out the bottom line, the numbers from the report imply that the world will hit a point of no return already by 2035—with a CO2 concentration of 482 ppm and a temperature rise of 1.6 degrees C.

In the EIA scenarios, the world does a pretty good job of migrating electric grids to renewables (or to some extent gas)—but a terrible job of moving applications to electricity. In developed countries this translates to business as usual, but in the developing world it’s much worse. India, for example, is seen as growing exponentially with much of the increase powered by coal. This isn’t just a question of forcing them to meet our standards. Heavy industry is a particular problem everywhere.

So the application area is a big job with many industry-specific issues. The world desperately needs focused research efforts with results that can be applied large-scale worldwide. This can’t be a matter of everyone guarding discoveries for national advantage. Cooperative international arrangements will be key to meaningful progress.

Even at this high level there are a number of conclusions to be drawn:

– There is no do-nothing alternative.

Technology will deliver a viable future, but we’ll have to work to get there. There’s no silver bullet that makes it all go away.

– Technology development is important and has to be figured into any planning, but technology concerns are not the barrier to success.

It is perfectly possible to put together a plan to get the US where it needs to be by 2030. That’s not saying all technology problems have been solved (after all electric cars are still much too expensive), but we can see a path to success. We shouldn’t trivialize the effort and sophistication required, but based on where we are, and given financing, it appears that the technical side can get done. The next point is less clear.

– Changes are huge and have to be dealt-with politically.

This isn’t just a matter of coal-miners losing their jobs. Electric cars alone will have pervasive consequences. We have to understand that worries about change are rational, so an important part of domestic climate policy has to be an assurance everyone will be made whole. Otherwise we will continue to face the push back seen most recently in the Australian election.

In the US there is every reason for the less advantaged to distrust the political powers that be. In the developing world it’s even worse—you’re talking about giving up on the benefits of development for some unknown duration. The situation is necessarily difficult. It’s only going to work if wealthy people and wealthy countries realize it’s in their own interest to come up with the goods. No one will escape the consequences otherwise.

– The international side is unavoidable.

There is only one atmosphere. Every country in the world has to cooperate, or we all lose. When the US opts out, everyone loses faith in the future—as was evident in the recent Madrid meeting. We have to restore international unity in order to make progress. And that will only come when every country sees a just role for itself individually. As for the terms of the Paris Agreement—it is only a first step and actually better for rich countries than will ultimately be workable.

We cannot go into this with the attitude that the objective is to come out a winner at the expense of everyone else. If everyone doesn’t win, we all lose.

– This is not a matter for incrementalism.

We’re not going to get there with well-meaning people insulating their houses or businesses putting solar cells on the roof.

It’s worth putting some numbers on this. With current technology, the power output of a solar cell is 20 watts per square foot. From that you can calculate how many solar cells would be needed to meet current US electrical demand. The answer is about 2500 square miles, assuming they’re all in brilliantly-lit, weather-free Arizona. (And there are serious problems in managing that one too.) All of it gets an order of magnitude worse if we decide to go piecemeal in random, less promising locations–and that’s just for today’s electrical grid, not where we have to get to.

That’s not to say that Arizona is necessarily the solution. The point is that there has to be a rational national policy that will actually get the job done.

Greta Thunberg is right—there is no substitute for major political action. Anything less is delusion, regardless of who says it. The 2020 election is the single, deciding climate issue today.

Perhaps we need the right metaphor. The fight against climate change is a war. We’re all in it together—losing is losing for everyone. The countries of the world are allies in the sense that each of them is necessary for success. National economies will be affected, but through national climate efforts with no shortage of jobs.

Right now we’re like the US in mid 1941. We can see and understand the enemy, but we’re not convinced we really have to be involved. That situation only got resolved when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, and it was clear there was no other choice. You can make a case we were lucky that it wasn’t too late. Without the Nazi’s disdain for “Jewish physics”, they might even have gotten the bomb.

For climate, if we act today we have the elements of victory. We also have ample evidence it’s a near thing. A climate Pearl Harbor may well be too late—and beyond anything we want to live to see.